North Dakota Pipeline draws controversy, social justice concerns

The North Dakota Access Pipeline controversy continues to pit oil industry developers against Native Americans tribes and social justice advocates

December 5, 2016

When asked to write an article on the North Dakota pipeline, senior Malyka Musso appeared puzzled and confused, “What’s wrong with the North Dakota pipeline? Wait, what is the North Dakota pipeline?” The lack of knowledge about this topic is not surprising as it fails to make the evening news for more than a few seconds, overshadowed by reactions to the presidential election and what Kim Kardashian wore. However, outrage from Native American tribes and their supporters over construction of an oil pipeline has brought increased awareness to what they believe to be an injustice.

Over 2.4 million miles of pipeline currently exist in the United States. The Dakota Access Pipeline, under construction by Energy Transfer Partners, will ultimately extend 1,170 miles from North Dakota to Illinois. The Standing Rock Reservation contends that, when finished, the pipeline will encroach on sacred Indian ground and will potentially ruin the reservation’s water supply.

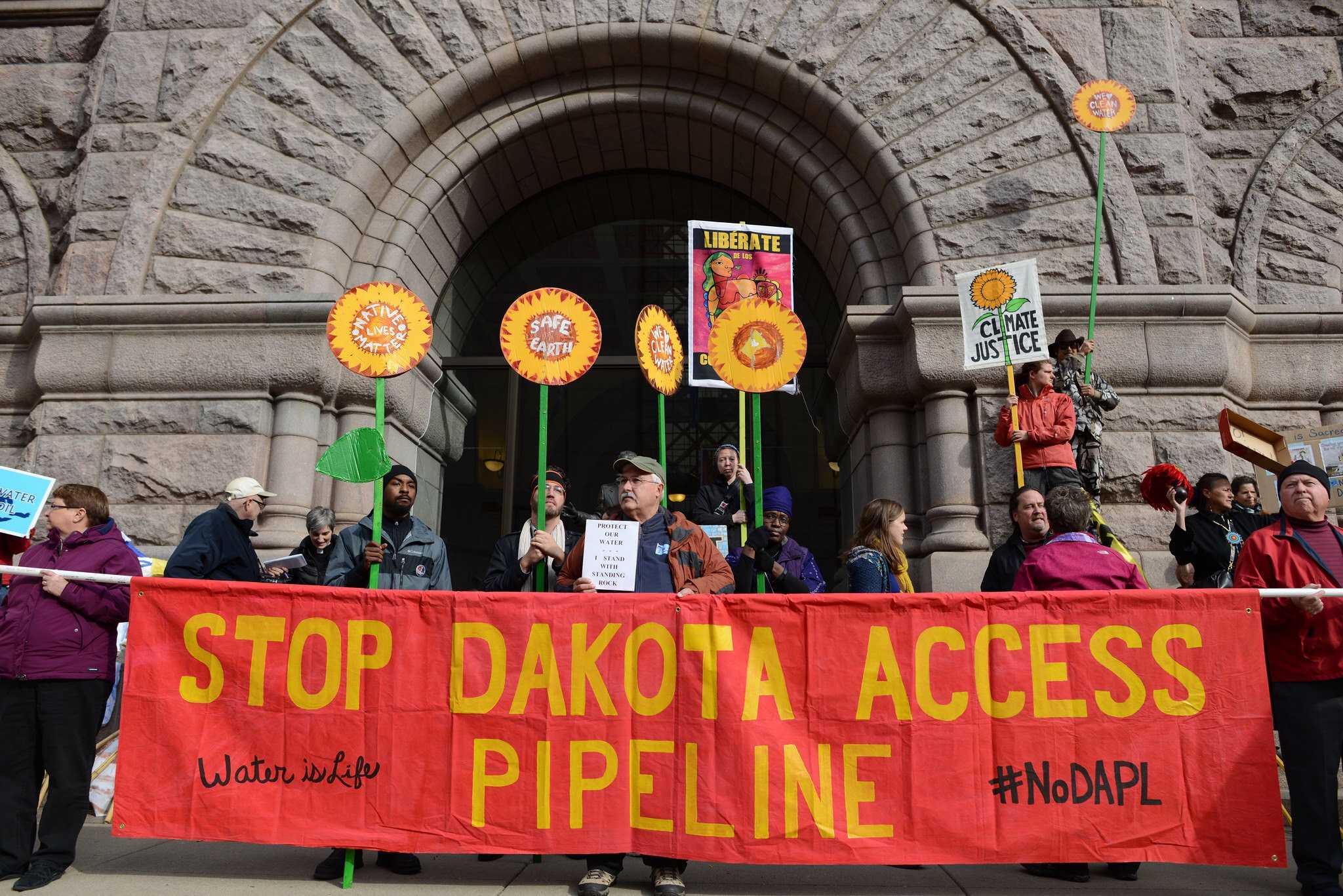

Protesters in Fargo, North Dakota, protest the NDAP. Demonstrations are not isolated to any one state as the issue is seen as an injustice across the nation.

Established in 1868, the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, one of the largest in America, is located in North and South Dakota. Both the Hunkpapa Lakota and Yanktonai Dakota make up the Standing Rock Sioux tribe, a functioning community of about 8,500 people.

After reaching out to the company and being repeatedly ignored, the Sioux began protesting the pipeline. Native Americans, as well as non-Native Americans, from across the country have joined the pipeline protest. The Standing Rock Sioux had sued the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the government agency responsible for approving the pipeline, saying that the U.S. Army Corps failed to take the appropriate steps to protect the environment and culture of the reservation.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers disagreed, saying the pipelines are very safe and “it is far safer to move oil and natural gas in an underground pipe than in rail cars or trucks,” also noting that Energy Transfer Partners’ pipelines have a very good track record and rarely burst.

Although the Sioux are worried about their safety and sacred grounds, there is a need for the oil that the company wants to transport. The entire country relies on oil and, if there is no access to it, local economies will suffer. The pipeline creates thousands of jobs; however, very few are permanent.

The Sioux tribe argues against the reliability of the pipeline. If it were to burst, it has the possibility of spilling hundreds of thousands of gallons of oil onto their land and into their water sources. This would create an even bigger issue, one that threatens the lives of those living on the reservation.

Mr. Richard Sistek, AP Government and Global Studies teacher, believes it is a complicated issue that can be looked at from more than one angle. From one point of view, Mr. Sistek said, “Oil and gas production in America is essential to our economy and the livelihood of all its citizens.” But he also recognizes the potential environmental and cultural issues the pipeline holds. “If a proposed pipeline route poses a purposeful or abusive disregard for the local environment or people’s lives, then another route should be designed,” he noted.

Mr. Sistek is not the only one who feels like this. North Dakota native Neal Garland also recognizes that there is no one clear answer, saying, “On the one hand, the pipeline would provide an important boost for the nation’s economy. On the other hand, to build it through the Standing Rock Indian Reservation against the will of the Native American people who live on that reservation would serve as yet another example of how the government has repeatedly placed financial matters above the desires of Native Americans.”

About 200 people gathered outside Minneapolis City Hall to protest the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Garland brings up another good and often forgotten point. The US government has a history of neglecting or ignoring numerous agreements they have made with Native American tribes, going back to the very beginning of European settlement. Many believe state and federal governments make choices that financially benefit them or private businesses and ignore the effects those decisions may have on indigenous people.

One of the biggest outrages towards the pipeline stems from the original route plan. The pipeline was supposed to go through Bismark, North Dakota. However, after complaints from the predominantly white citizens of Bismark, the pipeline was rerouted through the Standing Rock Reservation with the expectation that few would care.

The Standing Rock Sioux are not the first to experience challenges to their sovereignty, and they certainly will not be the last. After a year of going back and forth with the Army Corps of Engineers in court, a judge ruled that the tribe had failed to prove that the pipeline presented a clear danger. After the judge ruled and protests continued, the federal government was forced to step in. Over the past few months, protests have escalated and become more dangerous, with police using dogs, pepper spray and fire hoses in attempts to disperse the crowds.

President Obama, who had remained relatively silent, finally spoke out about the pipeline, announcing, “We are monitoring this closely. I think as a general rule, my view is that there is a way for us to accommodate sacred lands of Native Americans.”

As resistance continued, awareness has grown, which is essential to the protests. However, the police and Energy Transfer Partners are losing patience, eager for the protests to stop in order for the pipeline to continue.

Since this article was first written, construction of the pipeline has officially been put on hold. According to CNN, the US Army Corps of Engineers has called on Energy Transfer Partners to assess the current route and offer alternatives. Although the issue is far from over, this is certainly a victory for the Native Americans and social justice advocates espousing the cause.